Catastrophic forgetting

This post (my first post!) is about the work I did during my internship at Telefonica Research (@TEFresearch), advised by Joan. The goal of the post is just to make a an introduction to the topic of catastrophic forgetting, and provide a brief overview of our paper. A previous post by my colleague Marius inspired me to write something on the topic, and my advisor's recent presentation of the paper in the ICML conference in Stockholm was the perfect excuse to get the blog rolling. You will find the video of Joan's talk at the end of the post.

The problem

The idea of catastrophic forgetting appears not only in neural networks, but it is general for all machine learning (ML) algorithms. Thus, the best way to understand what catastrophic forgetting is, is to start by revisiting what do ML algorithms do. Broadly speaking, ML algorithms' goal is to find the optimum value of some parameters that define a function, so that the output of this function fits a certain (given) data according to a criterion. Then, once the parameters are fixed and the function is defined, ideally this function will work properly with (will fit) new data, this is, for new data, the criterion will also have a good value. This is called "generalize" to new data.

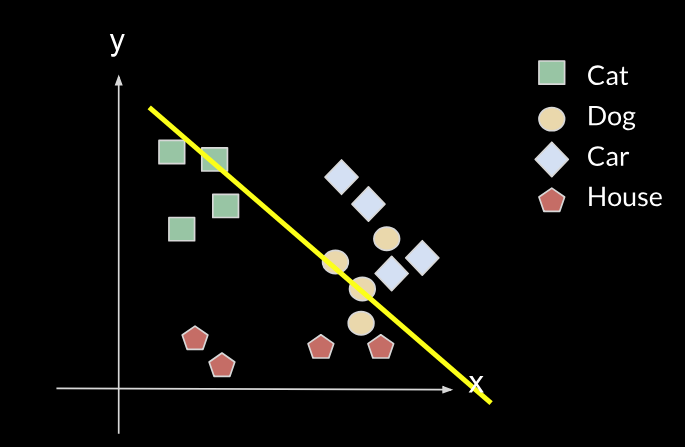

A very simple example is a linear classifier with two parameters, which could be the slope and the y-intercept of a line, and we have to choose the right value of these parameters so that the line can correctly classify 2D points into either class A or class B (above or below the line). For example, let's say we want to classify between cats and dogs, given two features X and Y (such as height and weight). From the data we have, we can train an algorithm that will give us a line such as the yellow one.

However, when we are presented with a new task, such as the task of classifying between cars and houses, we will need to change the parameters of our line (move the line), as shown in the following images:

The new line will no longer fit the initial data, it will no longer classify correctly between cats and dogs, so it will have forgotten the first task. This is what is called catastrophic forgetting.

This may not be a problem for a simple system like the previous one, because if we want to remember the initial line, we just need to save two parameters. However, in more complex systems where we want the different tasks to interact, and the number of parameters is of the order of millions, we cannot just maintain the different tasks completely separated. So we need a way of adapting the parameters of the first task so that they can also fit the second task while remembering how to do the first one. Also, the fact that the two (or more) tasks can be done by the same network allows some information to be shared between the tasks, potentially helping each other.

Back to neural networks

In the case of neural networks, several methods have been proposed. There are two main approaches to this problem:

-

Rehearsal. Here the idea is to use some memory to be able to replay the previous events (previous tasks).

A basic idea of this method is to keep some representatives of each class for previous tasks, and use them to

retrain the network.

- Pseudo-rehearsal. A variant of the rehearsal method is not keeping any memory of the specific samples, but instead training a generative model that can create samples from the previous tasks, and use them to replay the previous events as we train new tasks.

-

Reducing representation overlap. Instead of using the same parameters for all the tasks, an alternative

is just sharing some parameters that are important for different tasks, and then having parameters used by just

one task.

- Structural regularization. The previous goal is attained by adding a term to the loss to preserve important parameters.

- Freezing parts of the network, protecting them once learned.

Our approach

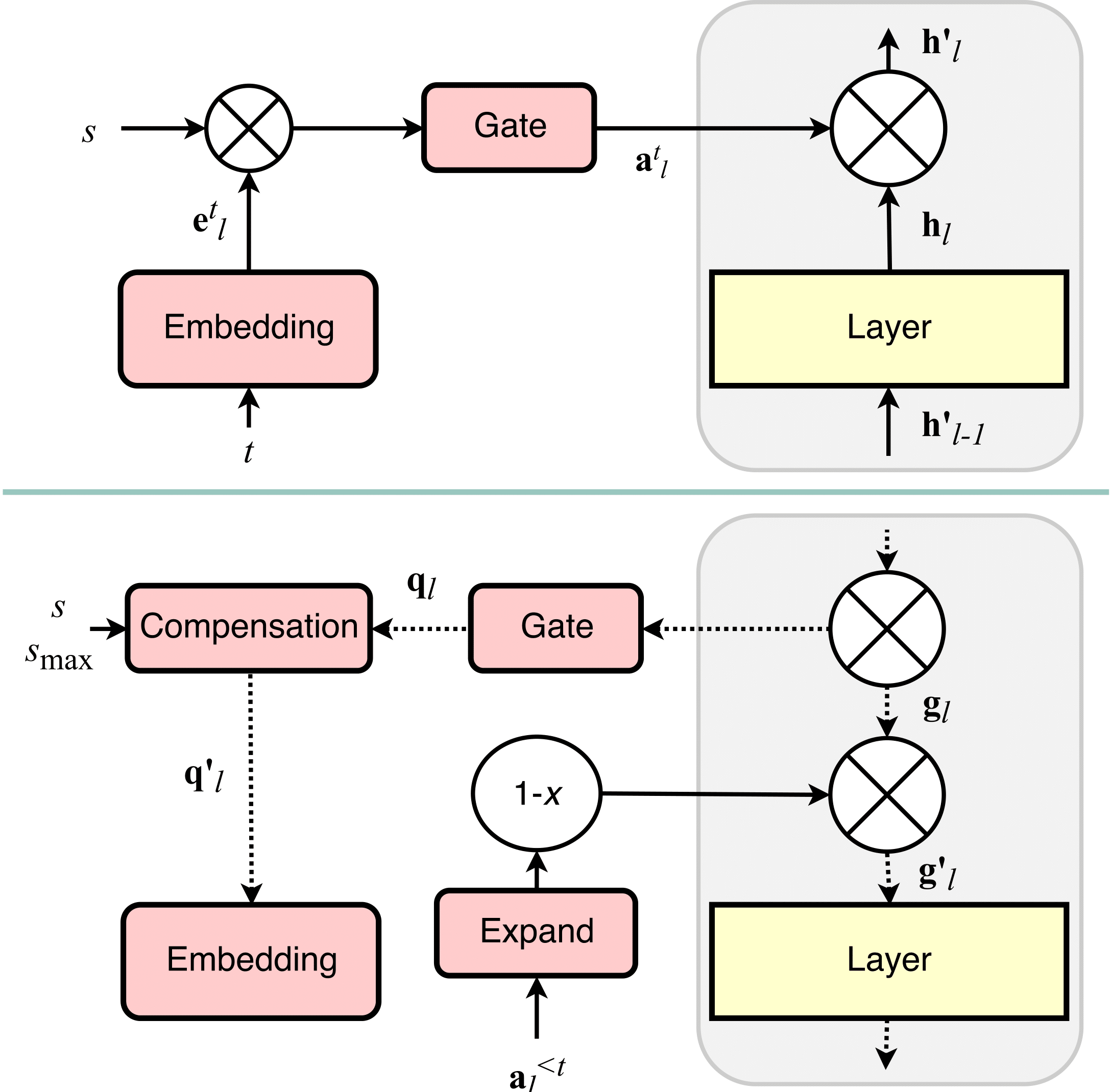

Our method fits into the second group, and combines protecting different parts of the network with reusing different parts of the network. We name it Hard Attention to the Task (HAT). The main idea of our approach is to use the id of the task to mask the activations of the units according to a mask, where each task has its own mask. The amount of parameters needed for the mask is negligible compared to the total size of the network. This mask is just a multiplicative term to the units, as the following GIF shows.

The GIF shows the following process: when training task 0 (pink), with an initial empty mask, we also compute what units of the system are really important for that task, and we fix them. Then, when training for a second (yellow task 1), we fix the units that were important for task 0, and also compute the units that are important for the new task 1 (while training the normal white network). Obviously, the new task can use the previously fixed units, but it cannot modify them, or else we would forget about task 0.

The training of the system is represented in the following figure, where we can see that the mask and id embeddings are just an extra branch trained together with the original network.

Two hyperparameters that control the system. Smax is the amount of closure of the sigmoid gate, which means that it controls the amount of forgetting of old tasks to make room for the new ones. c is the amount of compression we apply to our models. We add it as a regularization term in the loss, penalizing large masks. A large c will give room to more tasks, but will compress a lot these tasks. In the end, we have a fixed amount of parameters, and thus a fixed amount of capacity, so this tradeoff is completely logical, and is directly translated into these two understandable hyperparameters.

The way we fix the important activations is by multiplying the gradient by the opposite of the mask, so if the mask is high (value close to 1), the gradient for all the parameters affecting that unit is multiplied by a value close to 0, and so they don’t change.

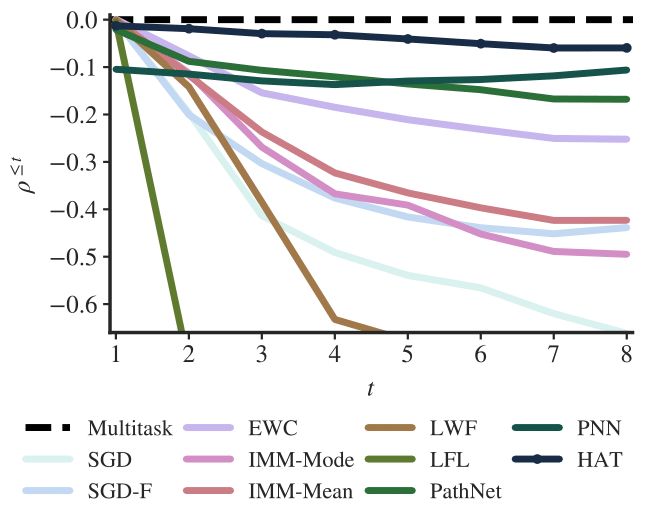

The results of our method are very promising, and actually beat the state of the art. The details for the following graph are in the paper, but basically it shows the amount of forgetting each method has, where the closer to 0 (which represents the joint training baseline), the better.

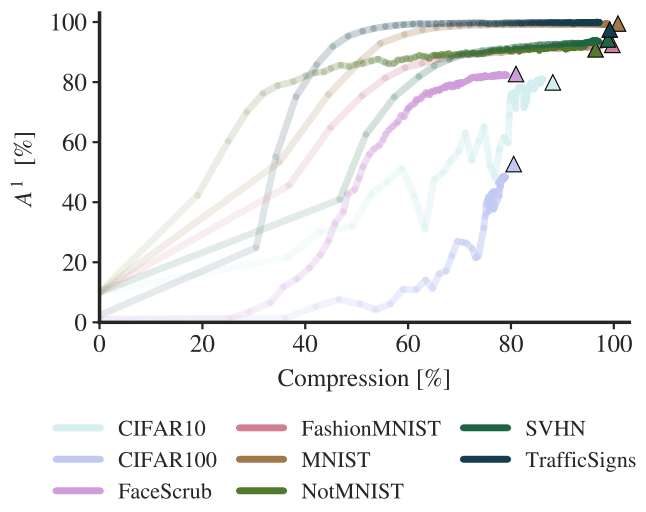

Also, the method works pretty well for network compression (as a nice secondary effect). As we train the network to compress the information representing each task (controlled by the hyperparameter c), what it does during training is first learning how to do the task, and then compressing the learned information into a few parameters. The evolution of the accuracy and the capacity occupied by each task during training is shown in the following graph.

So this is it! If you have any questions, please don't hesitate to send an email to any of the authors, or post a comment below, and we will gladly answer.

Finally, as promised, here is the video of Joan's talk (min. 21):

Leave a Comment